The Pentagram, Its Forms and Features

- The Pentagram

- 01 - Introduction to the Pentagram

- 02 - Structure of the Pentagram

- 03 - Pentagram Magic [PENDING]

- 04 - Pentagram Analogs and Substitutes [PENDING]

Having set aside most of the narrative baggage, we can now dissect the iconographic features of the pentagram.

To maintain the thread of the discussion, we reiterate our own working definitions.

Pentagram (Holotype) - A five-pointed unicursal star, usually placed inside a circle.

Pentagram (Gloss) - Any magical sign or figure.

Pentagram (Religious/Occult) - An abstract representation of the universe (cosmogram), in whole or in part, articulating Totality.

Pentagram (Magician’s Tool) - The stage of magical action.

Pentacle - A pentagram (any of the above), usually (but not exclusively) referring to a worn article.

I. Standard Breakdown: The Five-Pointed Star

We'll start by breaking down the holotype—a five-pointed unicursal star placed within a circle.

The circle receives its own attention later in this article, but we can quickly address it here: the circle represents the world, universe, eternity, or Totality. It can get more complicated and particular, but for now, this will suffice.

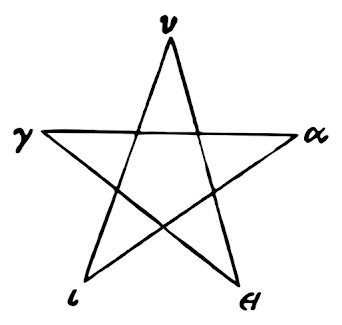

The star is typically unicursal (drawn without removing the implement from beginning to end). The ancient Greeks called this the "pentalpha," as it could be formed by laying five capital "A"s one over the other. It is also called the "eternal knot,"* with "knot" being a common descriptor of unicursal designs (such as "Celtic" knots).

|

| Despite popular association, these knotwork patterns originated in the Roman Empire, spreading throughout Europe and arriving in Scotland and Ireland relatively late in their development. |

*(Compiler’s Note: the term "eternal knot" could also be read into the pentagram's application in sorcery, re: the "knot" being used to "bind" spirits to service. While we have seen no evidence of this interpretation being employed in the historical record, we would not be surprised if a latter-day practitioner read this meaning into it. Further, its lack of historical precedent does nothing to stop you as a storyteller from employing such an interpretation.)

The fact that the pentagram's five-pointed star is a star is significant, signifying something celestial. The celestial connection operates in two primary ways: either as a direct representation or stand-in for the celestial (e.g., the course of Venus, as discussed in the previous article) or as a reflection of transcendent principles.

This reflection property can work along two axes of consideration: direct reflection, like a mirror, or internal-external, as all cosmograms play with the microcosm/macrocosm dynamic de facto.

|

| The Seal of Solomon, as the frontispiece of volume 1 of Lévi’s Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie. |

The pentagram also has a layered relationship with the five elements, serving as a representation of elemental Earth while also acting as a stage for all five elements. We have already covered this dimension in detail, but it is worth reiterating that our readers should revisit the elements. Most often, if you’re not using the pentagram as cheap shorthand for Satanic/sorcerous activity, it’s going to be related to the elements.

The Pythagoreans identified each other by this sign because it was a recursive fractal of the golden ratio and the numerological basis for the Western pentatonic musical scale (as discussed in the previous article). They also wrote the word UGIEI (meaning “health,” “soundness,” “divine blessing,” etc.) around the edge, read clockwise (and later the Latin for “health,” SALUS).

|

| Here, we see the Pythagorean Pentagram, the model for many pentagrams and pentacles, dating back to the 6th century BC. |

The writing around the edge will be revisited later, but suffice it to say that the five-pointed star has associations with the transcendent qualities of mathematics and divine geometry. This lends it something like a laterally transcendent quality, making the pentagram magically workable even if one isn’t trying to reference the superior and inferior dynamics of heaven and earth.

We spent much of our previous article tearing down the dogmatic imposition of fixed meaning in the pentagram’s orientation. Here, we have to affirm that orientation is a valid dimension of exploration and expression. While our readers are not beholden to the dogma, they understand it’s now part of the conversation. For that reason, we must address how orientation functions within this expanded information ecosystem.

|

| Stanislas de Guaita's pentagrams from La Clef de la Magie Noire. |

If the points are identified with the five elements, and the context suggests the vertical point is indicative of “spirit,” then orientation can be validly determined by the practitioner as necessary, “practitioner” here is limited to the person with the agency over the pentagram’s creation and context—the maker, wearer, builder, or any committee thereof that determines its intended meaning. The witch who wears the inverted pentagram decides that her necklace is a symbol of her rejection of conservative religious dogma and taboos against sensual pursuits. At the same time, the church builders and responsible clergy determined that the inverted pentagram in their place of worship is indicative of divine communion between the Divine and Man (as at Amiens Cathedral). Both are valid in their contexts.

One may differentiate between an orientation that changes its environmental context regularly (such as an article of jewelry) and one with a fixed context (such as an architectural feature). A pentagram without a fixed environment for interpretation may be understood to lack specific contextual clues and, therefore, default to a more fixed interpretative framework.

Another consideration often overlooked is how people can change their context. In a possession movie, the malevolent spirit or demon will knock over or turn wall-hung crosses/crucifixes as a sign of disrespect or to try to convince the family they are terrorizing that “God isn’t here.” While this is symbolic communication and not an example of practical magic (it doesn’t demonstrate an action that produces a novel effect), that doesn’t mean such an action cannot be employed in practice.

Consider that a pentagram, as a device, is often depicted as a disk or medallion. As a round article, it may be rotated. Presupposing that a magician has constructed an iconographic environment in their own home, a malevolent actor might change the orientation of one of the Magician’s active environmental pentagrams to disrupt the carefully constructed magical environment. Alternately, in a more comedic narrative, a magical utility worker could enter the Magician’s home and go, “See, here’s your problem, you stored your pentagram upside down. Common problem, easy fix. That’ll be $450.”

In a context where magical practice is active and dynamic, such as urban fantasy prose or a video game, the practitioner might deliberately change the orientation of their pentagram to alter the effects of their spellwork or open up different options. Continuing with the game mechanics example, this could be akin to pressing a button to toggle access to other abilities tied to the controller’s D-pad.

Using the above formulation, if one wishes to continue the up-good/down-bad formula, an upward pentagram might be used for healing/protection and an inverted pentagram for offensive spells. Suppose one wishes to remove the pentagram orientation from moral charge while retaining the “spirit” identification of the vertical point. In that case, they might interpret it this way: the upward pentagram evokes the elemental spirit energy out of reagents in outward and immediate magical expression (offense, curse, ward, protection, etc.), while the inverted pentagram imbues a material or tool with elemental spirit, enchanting the device or material with a lingering magical effect.

Finally, we must also consider the aesthetics of orientation.

The identification of the inverted pentagram with the horns of the Sabbatic goat has more than a simple shape parallel. The reality is that the inverted pentagram just looks more aggressive than the normal orientation. This suggestion of aggression is a valid read in iconographic shape language. The inverted pentagrams in churches are usually positioned above the heads of the congregants, so when you look up at them, you understand the directionality. An inverted pentagram at the body level also has its points at the body level, which could be read as threatening to pierce the viewer. In short, those above the level of the head suggest divine descent, while those at the body level suggest confrontation.

As observed by many, the upward-oriented pentagram bears a vague resemblance to the shape of the human body. This has led to many anthropomorphic expressions of the pentagram that warrant further exploration. We have Le Guaita’s Adam-Eve Pentagram:

In our last article, we went over enough of this one’s meaning by contrast to the goat-head pentagram. While we’ll explore the dimensions of its magic circle later in this article, suffice it to say there isn’t much that is illuminating in this one’s anthropic expression that is not better communicated by older examples.

|

| Anthropomorphic pentagram from Agrippa's Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Book II, Chapter 27. |

Here, we see an older expression of the anthropic pentagram that predates the orientation dogma. Free from a forced contrast with the Sabbatic goat, we can engage this as what it really is: an identification of the human body as a cosmogram. This is a geometric interpretation of the idea that Man is made in the image of God by expressing Man as a subordinate model of reality.

|

| Lévi’s "Blazing Pentagram" from Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie. |

Anthropic pentagrams are not inherently magical. Lévi’s “blazing pentagram” is a pedagogical and rhetorical device expanding on the ideas of the earlier anthropic pentagram. By employing more abstract imagery, he utilized it to highlight the self-awareness of the anthropic microcosm-macrocosm connection, thereby conveying occult enlightenment.

Understanding whether a “magic” symbol is being used magically or as an instructive diagram may well be critical to your storytelling. Still, another dimension of this is worth considering: The enlightened magician already understands that their body is a pentagram.

The increasing sophistication of magicians, as they develop their art, may be a result of the growing level of abstraction in their magical practice.

We’ll bring in some role-playing mechanics from Dungeons & Dragons as they relate to wizards.

|

| 2nd edition spells got pretty wild. |

Wizards can cast a certain number of spells per day. They do not possess a pool of magical energy that can be replenished by a potion, as seen in video games. They instead have to perform all the spells the night before, except for the final trigger, and have all their previous spellwork memorized. As the wizard develops, the time available to memorize does not change, but they can memorize more spells at increasing levels of sophistication and in each category of difficulty.

While memory improvement and familiarity explain some of these dramatic developments in efficiency, a more specific and character-oriented answer is that they develop a sophisticated shorthand. Seeing that a spell calls for the drawing series of complicated pentagrams, the advanced wizard may simply substitute their own body and a few referential gestures in the preparation, skipping many steps and saving themselves a lot of time.

In visual storytelling, the novice magician may have to pore over tomes and carry drawings and diagrams with themselves everywhere to effect even the simplest spells, while the masters of the art accomplish things far grander with only a few subtle gestures.

Perhaps more evident than the human body as a pentagram is the hand, which also forms a pentagram. This is, in many ways, similar to the anthropic pentagram and can work alongside and in tandem with it, but it also possesses interesting qualities worth considering.

First, this indicates “possession,” that the universe is held in the hand. This is well illustrated in an example outside the Western tradition, in the classic Chinese novel "Journey to the West."

|

| Anonymous art for the 19th-century Chinese work Illustrations for the Original Gist of the Journey to the West (西遊原旨圖像 Xiyou Yuanzhǐ Tuxiang). |

In the story, the Monkey King Son Wukong is causing a ruckus in heaven, and no one can stop him. Buddha is sent in to address the situation. Buddha challenges Son Wukong, saying he bets that the Monkey King can’t jump out of his (Buddha’s) palm.

Wukong accepts the challenge by immediately jumping onto Buddha’s palm and launching himself out to the edge of the universe. As he passes through the sky, he’s smug, seeing that he’s rapidly approaching the pillars of heaven. He is then sorely disappointed when he collides with one of the pillars and realizes that it’s one of Buddha’s fingers. He is summarily punished by having a mountain dropped on top of him for his misbehavior.

Here, we see the microcosm/macrocosm dimension played for laughs. Buddha’s palm is the universe in microcosm because, as an enlightened and transcendent being, he holds the universe in his hand. To a figure like the Buddha, any observed difference between his palm and the whole universe is a failure in the observer’s perception.

While this effectively models the microcosm/macrocosm’s relationship to enlightenment, this concept lends itself to comedic exploitation. In Stephen Chow’s film Kung Fu Hustle (2004), the main character, Sing, a loser, is a petty crook who has memorized the “Buddhist’s Palm” style from an old pamphlet. The style is regarded as useless, and Sing is even more so. Lampooning kung fu media conventions, it turns out the loser Sing is actually a natural kung fu genius, and he only needed his ass kicked the right way to unlock his qi channels. In the end, he defeats his enemies without needing to touch them (literally), crushing them at a distance with the “Buddhist Palm.”

Beyond the possession and transcendent qualities, we also have the qualities of the hand itself to consider. This broader subject will be covered in depth in our article on [anthropomorphic symbolism], so we’ll limit this exploration to hand chirality.

The right (dexter) and left (sinister) hands have different dimensions of consideration, similar to up-down orientational thought. One could characterize the right hand as “giving” and the left as “taking,” or prioritize the right hand as “clean” and the left hand as “unclean” (based on the common practice in many cultures to wipe with the left hand after defecating). This interfaces well with orientational thinking and characterizations in occult circles of the “left-hand path,” and so on. This could also influence gesture-based magical systems, especially if the hands are used as analogs for the pentagram.

II. Standard Breakdown: The Circle

As mentioned earlier, the circle is a symbol of the world or universe in Totality. The circle is an unbroken line without a beginning or end, and the only geometric shape without divisions, being uniform at all points. The circle is indicative of perfection, unity, completion, and eternity. This makes the circle emblematic of the immortal Platonic principles, being both stable in their unmoving, perfect forms (the stasis of shape) and dynamic in their material expression (the cycle of time).

|

| A circle (in case you weren't aware). |

The circle shares all of this symbolism with the point, an emblem of the Monad (the One, supreme divinity, ho theos, the Tao, “God” with a capital “G”). This observation was recognized explicitly in Neo-Platonic thought, where it was identified with the uncircumscribed cosmic center, the principle of Being from which existence flowed. The circle is not a boundary placed on the totalizing Monad but an emanation of the fundamental cosmic source, pointing to the divine paradox of the infinite source.

While the point and the circle share many properties, in practical terms, the circle offers more room for novel expression. By occupying more space than the point, the circle has a larger iconographic surface to work with, offering greater opportunities for reframing, recontextualizing, and reimagining. Other important symbols, including the wheel, the disc, the ring, the clock, the sun and moon, the ouroboros, and so forth, all manifest the universal shape and its qualities in particular contexts with their own unique considerations. However, their shared participation in the circle enables these particular forms to interact, substitute for one another, and synthesize with each other.

That final point is crucial for you storytellers and artists, as symbols of shared form can absolutely be swapped out for each other in magical working by substitution, re-characterization, and innuendo.

We’ll illustrate with a liberal use of an Icelandic stave: the Ægishjálmur, or “Helm of Awe.”

|

| The most common iteration of the "Helm of Awe." |

As mentioned in the previous article, the Icelandic staves mostly date from the 16th and 17th centuries and are, therefore, thoroughly post-Viking. The stave above is influenced by continental grimoires, such as the Clavicula Salomonis.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not referencing something in Norse mythology. In the Völsunga saga, the prose Reginsmál, and the Fáfnismál section of the Poetic Edda, there is a physical helmet called the Ægishjálmur, alternately translated as the “helm of awe” or “fear-helm.”

This makes the stave a mythological reference, which is perfectly valid in religious and magical iconography, even if its expression hails from a radically different tradition. Furthermore, artists and storytellers will seize anything in sight, even tangentially related to the subject, as aesthetic filler to meet their own and their audience’s stylistic demands. General audiences will absolutely accept this anachronism with “Viking” characters.

Accepting that, our sample nasty “Viking” has chosen to wear this Ægishjálmur wheel on his helmet.

The choice of “wheel” here is significant because it provides many opportunities for iconographic synthesis. Not only is this “helmet” being used as a protective amulet on our Viking’s literal helmet, protecting him and granting him a fearsome countenance, but the characterization of a wheel makes it a part of the chariot of Thor. This character transforms the manifestation of his desires into a subordinate clause to the will of the divine spirit of the Warrior!

The symbol’s connection to the Fafnir provides further synthesis, bridging the wheel to the serpent ouroboros and the dangerous potentiality of the dragon. This asserted hypostatic union of divine warrior and monster prompts character arcs.

On the one hand, it’s a challenge to those who fight the warrior. “Who are you?” it mocks, “No god and no Sigurd, surely!”

On the other hand, this is a classic model of hubris, as identifying with both the warrior and the dragon demands a response from Thor, who is bound to chaoskampf at Ragnarok with the serpent Jormungandr.

Moving away from particular iconographic devices like the wheel and the snake, we return to the circle in its abstract geometry. Removed from a context of tangible tools, the circle works in the realm of ideas.

What does any of that mean? What are we talking about?

We are referring to the employment of numbers, names, shapes, figures, caracteres, and any other writing or marking at the edge of the pentagram’s circle.

|

| These 'uns. |

The Pythagorean UGIEI/SALUS amulet set the model for Western pentagrams by using this phrase, meaning “health/soundness/divine blessing,” particularizing what they wanted to evoke out of the pentagram’s mathematical harmony.

That’s the secret of the edge-writing: it just makes the circle more particular.

The Pythagoreans wanted something out of the pentagram, but given its role as a cosmogram, it’s more often used to indicate jurisdiction over something in the pentagram. Revisiting La Clef de la Magie Noire’s pentagrams:

|

| We're getting a lot of mileage out of these. |

Here, the “good” pentagram is identified with Jesus Christ (Yahshuah) by a Pentagrammaton, YHShWH (יהשוה). The “bad” pentagram is marked for Leviathan, the primordial serpent enemy of God, by a similar Hebrew Pentagrammaton, LVYTN (לויתן).

Here, we see a pedagogical use of the pentagram, as these markings indicate the orientational jurisdiction of the spiritual Savior and Enemy.

This jurisdictional thinking isn’t merely a feature of magical instruction but of practice, as many of the pentacles in the Solomonic grimoire tradition and more modern High Ceremonial Magic employ names of power. These may be names of God, pagan gods, angels or demons, astrological figures, and so forth. These may express dominion over the thing described within the interior of the pentagram, control of the boundary between the realized material world and the unrealized spirit world, hierarchical power, and so forth.

|

| The Second Pentacle of the Sun, bearing the names of the Angels Shemeshiel, Paimoniah, Rehkodiah, and Malkhiel. |

But it’s not just names; it’s also magical and astrological figures, verses of scripture, magical caracteres and voces magicae expressed in cipher, powerful geometric forms, or explicit statements of function in plain language.

Depending on how the pentagram is being used, these markings, writings, and invocations can serve multiple purposes. If the pentagram is being used as a ward or a threshold, the markings may state that lines cannot be crossed under the jurisdiction of such and such, or by invitation of God’s wrath, or any other such formulation.

Alternately (and perhaps of interest to you, fantasy writers), if the markings are given by a tutelary spirit, they might be a cipher that filters out any familiar spirit not sent by the tutor. A spirit in affiliation with the tutor should have the key to cross the threshold. (wink, wink)

As tools of action, these circle markings provide opportunities for a great deal of magical instruction, a kind of programming that might maximize intended effects and limit interpretation of the interior iconography.

They might also be indicative of religious affiliation, as the edge can be used to express beliefs in cosmic hierarchies, calling on the whole heavenly structure to participate or leveraging the authority of heaven or hell.

More immediately apparent than the edge of the magic circle is its interior, a canvas that takes up most of the shape’s surface.

We have already discussed the five-pointed star as a symbol at length and have hammered home that many signs, seals, sigils, emblems, etc., have occupied the pentagram/pentacle’s interior.

|

| "Well, fancy seeing you here." |

The function here is simpler than the edge of the circle, though arguably more versatile: the interior of the pentagram identifies something in the world of phenomena.

The five-pointed and six-pointed stars (to be discussed later) articulate the 5 elements or the 5 elements in their relationship to the shaping/generating principles. These are totalizing and, therefore, refer to everything.

However, symbols placed within the circle adopt the categorical name “pentagram” or “pentacle.” This means that the totalizing iconography of the classic geometric stars is assumed, and therefore any symbol in their place is laid over the holotype icon in principle. That is to say, the five- or six-pointed star is presumed and accepted to be incorporated by innuendo.

Therefore, any symbol placed in a magic circle identified as a pentagram/pentacle identifies that thing as it manifests in the universe.

This can be a person, an identity, an idea, a material, an action, a reaction, a place, or anything else. To demonstrate this, we’ll examine a historical magical practice and a work of modern media: the lamen and Fullmetal Alchemist.

|

| The lamen from the Hygromanteia. |

In Western sorcerous practice, there’s a form of amulet known as a lamen, a kind of ritual breastplate or shield. The common ceremonial logic is that you tie the lamen to the spirit you are trying to summon so that it cannot harm you. This is accomplished by the use of the spirit’s seal, which is a magical caractere that identifies the spirit, placed within a circle, like the waxen seal of a signet ring.

This spirit seal is a pentagram because it is circular and identifies the spirit as a thing in the world. This is then placed on a small shield-shaped medallion. The logic of the lamen is clear:

Shield (protection from) + Seal (spirit in the world) = “I am protected from this spirit and all its manifestations”

Of greater interest to modern storytellers and audiences is the visually dramatic transmutations of the alchemists in Fullmetal Alchemist.

Aside from our show’s main characters, most state alchemists have a name that is indicative of their alchemical style. They develop mastery over a handful of transmutation circles for combat.

|

| Colonel Roy Mustang, the Flame Alchemist. |

Figures like Col. Mustang typically only have a pair of identical transmutation circles on or near their hands despite a wide breadth of alchemical knowledge. They utilize the creative exploitation of one type of reaction to solve complex problems, demonstrating both specialization and versatility.

Their transmutations are limited by the designs of their transmutation circles, which, if it’s not clear yet, are pentagrams.

|

| Mustang's Flame transmutation circle (left); Armstrong's Strong Arm transmutation circle (right). |

The transmutation circles of Fullmetal Alchemist are isolations of specific phenomena in the world, in this case, a chemical reaction.

For our own audience, we invite you to embrace this logic for your own storytelling and know that you can expand, limit, or alter the described thing (a spirit or chemical reaction) as appropriate to the story you’re trying to tell. Go for it!

This is commonly employed in modern media depictions of sorcery, but it is less common than people think. That said, it’s not without precedent in the tradition, as seen in works like the Liber Iuratus Honorii, or in more accessible folk beliefs, such as fairy rings.

|

| A fairy ring of Clitocybe nebularis. |

Magical circles can also be gateways. While we will cover this in greater depth in the [following article]’s section on historical conjuration, we have to plainly validate that reading here.

We will say, however, that exploration of the magic circle-as-hole could benefit from considerations from our section on the magic circle’s edge.

There are two major points to address here.

First, in case we didn’t make it clear in the Circles and Synthesis section, circles are also evocative of celestial bodies, both in particular and in place.

By that, we mean that particular celestial bodies, most prominently the sun and moon, appear to us as discs. Further, the space in which we perceive the celestial bodies, being the heavens where they reside and the earth where we observe, are circular spaces relative to human perception.

This is another layer of the pentagram-as-cosmogram, which is not particularly actionable in itself. It is more actionable, however, when we step up into our second point of consideration: the sphere.

Spheres are three-dimensional, as opposed to the two dimensions of the circle. This quality is more strongly indicative of substance due to its volume (and also aligns with the mystical properties of the triangle, another numerological expression of 3). This is iconographically a more aggressive shape of manifestation.

It also has even stronger cosmological dimensions relative to the Pythagorean model of the Harmony of the Spheres.

|

| The Pythagorean "Music of the Spheres." |

This is a round-Earth geocentric model of the universe, where the Earth is at the center (and therefore the bottom) of reality, with concentric spheres of increasing influence extending outward to the Absolute. This model’s fundamental presuppositions were preserved in the later Ptolemaic model, which survived until the Copernican revolution and so shaped nearly all the cosmological thinking of the Western magical traditions.

|

| The Ptolemaic Model |

This also aligns with the mathematical mysticism of the Pythagoreans, who focused on harmonics, as seen in the pentagram’s recursive fractal properties.

Rather than try to break down Pythagorean mathemagic, we’ll focus on the transcendent quality of the sphere as a cosmogram. Just as our synthesis observation of circular symbols rendered similarly-shaped devices into synonyms, the shared spherical shape of the different layers of reality renders them synonymous along the microcosm/macrocosm axis, allowing reciprocal engagement via the Hermetic Axiom: “As above, so below; as below, so above.”

Basically, you can use it to conflate heaven and earth into the same “place.”

Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that circles can and are used as two-dimensional representations of spheres.

|

| The "wheeled cross," "crossed circle," or "wheeled gamma cross," a Greek geometric representation of a sphere. |

This brings us back to the pentagram, which, as a cosmogram, is a circular depiction of a spherical universe. To those knowledgeable, you already have access to the meaning of the sphere by default; you just have to be aware enough to exploit it!

We also note that the previous observations extend to architecture: domes, vaults, and cupolas are actionable 3D pentagrams that shape the space of action. Don’t be afraid to actively engage architecture for magical mechanics.

III. Standard Breakdown: The Star

There are two dimensions of consideration for the stars often seen at the center of pentagrams:

- They are stars, as in the celestial bodies, and,

- The properties of the specific star

To the first, the matter is straightforward: stars are in the heavens and, therefore, divine. All stars are referents to the firmament, even in negative reflection (like "bad" interpretations of the inverted pentagram).

All things shown with a star or laid over a star by innuendo (see Circular Abstracts: The Center) are referential to the divine principle from which the manifestation flows. A star indicates that the thing so marked or framed is elevated, like the stars referenced.

To summarize:

Slap a star on it = Magic!

Slap it on a star = Magic!

|

| MMMMMMMMAGIC! |

The unfortunate reality is that there are too many specific stars, both in the number of points and in peculiar formulations, that we cannot even approach covering them all here. We have already covered the five-pointed star, and so we will limit our exploration to six- and seven-pointed stars.

|

| We'll deal with these another time. |

We chose this limitation because:

- Six- and seven-pointed stars are the most common, next to the five-pointed star;

- The other stars are almost entirely a function of the numerology of their points and are best explored in our planned [numerology] article; and,

- The six- and seven-pointed stars have enough baggage by themselves to warrant articles by themselves.

IV. Numbered Star Variations: The Hexagram

The six-pointed star is the most common pentagram/pentacle figure employed in occult iconography next to the five-pointed star, having historically outnumbered the holotype on occasion.

According to the [Jewish Virtual Library], the six-pointed star saw broad ornamental and possibly magical use in the Bronze Age, from Mesopotamia to Britain, and in the Iron Age from India to pre-Roman Spain. It did not feature in Jewish Mysticism until the Middle Ages, where it appears to have been internalized from Islamic and Byzantine Christian magical texts. This was conflated with the extra-biblical folk tradition of King David’s magic shield*, which initially was supposed to have borne the name of God instead of a geometric figure.

*(Compiler’s Note: This tradition of the magic shield of David likely stems from the Psalms attributed to David, where God is referred to as the “shield” of the psalmist. Taking something figurative literally is a method of making something magic as effectively as slapping a star on it.)

The hexagram is unique among the regular geometric star formulations in that its “regular” form cannot be produced unicursally. Instead, it’s the product of two triangles overlaying each other. This double-shape feature is the root of its dualistic associations. This is particularly important in occult and magical practice, where the paradox of the “union of opposites” is employed to identify or access the transcendent.

The upward and downward triangles are indicative of all opposing dualistic forces. Or, more precisely, whichever ones you’re trying to juxtapose at the moment. Celestial/earthly, spiritual/material, masculine/feminine, etc., are all expressed here. It should be noted that triangles, as the first proper geometric shape, are indicative of substance and form and so signify the manifestation of the described forces.

In the Western occult and alchemical tradition, the triangles are used to signify the four material elements, as discussed in our previous articles. They take the form of triangles or triangles with bars.

By overlaying each other, each triangle serves double duty, representing two elements that are categorically divided by their masculine (shaping) and feminine (generating) affiliations. Serving as the binary of the animating principle, the fifth immaterial element of aether/spirit also finds totalized expression.

This lends the hexagram to use as a pentagram that is more particular about the relationship between the elements and the world of manifestation, bringing a vertical axiality that is absent from the pentagram holotype. In Western Alchemy, it was also used on occasion as a distinct emblem of aether, highlighting the shared abstract quality of animation while excluding the material manifestation suggested by the triangles.

This masculine-feminine axial observation isn’t unique to the Western tradition, as it is also expressed in Indian mysticism through the formulation of the Shatkona yantra.

|

| A particularly fancy shatkona. |

In Hinduism, this emblem is identified as the union of the masculine Supreme Being (Purusha) and the feminine nature or causal matter (Prakriti). This is expressed abstractly via the masculine divine note of Om (upward triangle) and the feminine creative power of Hrim (downward triangle). These are most often personified in the forms of Shiva and Shakti.*

*(Compiler’s Note: While Shakti may be characterized as a goddess in her own right or as the title of another distinct goddess, Shakti is also an identification of the underlying forces that sustain material existence. The consorts of male deities are all Shakti, representing the material manifestation of the principles the male deity is identified with, characterizing instance and manifestation as the creative sexual union of divine abstraction and matter. Formulations like this are rampant throughout every mystical tradition this Compiler has had the leisure to explore.)

It’s worth noting that this Shatkona formulation bears a striking resemblance in form and substance to the Deus/Hyle diagrams created by Western occultists such as Robert Fludd.

|

| Here we see the triangle orientation substituted with the triangle as phallic relative to the feminine circle. |

The hexagram is employed in Hermeticism, the bedrock of formal Western magical and occult tradition, as an emblem of the fundamental Hermetic Axiom: “As above, so below; as below, so above.”

This plays into the vertical liminality of the icon we’ve already articulated in our discussion of the hexagram’s relationship to the elements. This liminality is likewise echoed in the symbol’s use in exorcism, as well as in sorcery to invoke and banish planetary forces.

The hexagram is also employed as a correspondence map in Kabbalah. Those applications are too particular for our purposes in this article to list here, save to say that any of these symbols can be employed as a correspondence map for your own storytelling purposes.

The unicursal hexagram has all the same associations as the standard, two-triangle hexagram, save that its lines aren’t uniform. Its universality evokes eternal continuity, but its lines give it an irregular quality. That, in itself, is worth exploring.

Aleister Crowley employed the unicursal hexagram with a five-petaled flower at its center in his practice of Thelema. Our acknowledgment of Crowley’s use is not to highlight specific practices but rather the aesthetic dimensions of the emblem. Crowley was a counter-cultural figure who employed a non-normative hexagramic icon, a visual deviation from the traditional hexagram of regular shapes and lines. Its angles are notably more acute than those of equilateral triangles, appearing sharper. This perceived sharpness is aggressive in character, much like the inverted pentagram when placed at the level of the observer.

Visually, this icon lends itself more readily to “dark” or “black” uses of its shape language. It’s more evocative of the “secret” knowledge of magicians through unicursality and the accompanying novelty.

Also, as a practical consideration, it’s easier to trace with the ritual sword.

For storytellers, while this device has valid, positive uses like any of these other emblems, its unique qualities readily lend themselves to identification with the “evil” or, at the very least, the “dangerous.” Do not hesitate to use it for such purposes.

As we’ve already pointed out, the regular hexagram can be interpreted in the passive or in the active as a diagram of the creative union of shaping and generating forces.

|

| A regular hexagram |

In the passive, it’s a description of the pre-existing product of the creative union, a dissection of the composition of things as they already are. In the active, you are calling for a creative union to occur and conceive a new phenomenal instance.

Which is being called on is usually contextually determined, or you may want access to both interpretations. But there is a way to make one’s intentions more straightforward:

|

| An "active" hexagram. |

We’ll call this an “active hexagram.” The placement of the triangles suggests they are moving into each other, approaching the position of the regular hexagram. This means the creative sexual union is in process, and therefore the diamond-shaped space between them is fertile potentiality awaiting realization.

For a demonstration of practicability, see Considerations for Writers: 10) Fullmetal Alchemist and Roy Mustang's Fire Transmutation.

Based on this Compiler’s observations, there are two dominant axes of consideration for the hexagram in magical storytelling:

- Duality; and,

- Vertical liminality

The first option is easier to explore, as it offers several choices. It may involve the expression of opposites or contrasts, a shared transcendent property, or creative interaction.

Dualistic expression does not need to be limited to complete opposites but may be rooted in situational contrasts. Fire and Air, for example, may be expressed as direct opposites in the framing of active/passive masculine, but are both elements that compose the masculine half of the vertical elemental hierarchy.

When identifying the transcendent shared property of both things referenced (in this example, the shaping principle), this might be used to bolster one with the other. In our Fire/Air example, it would be fueling the Fire with Air or increasing the air pressure with the heat of the flame.

In the creative interaction of dualities, we’re talking about manifestation from (abstract) sexual conception: the meeting of the duality to create a new, distinct admixture. With our fire/air example, it might be giving a flame the breath of life as an artificial elemental construct or something more abstract, such as breathing life into and animating a dead or dormant passion.

The second option, vertical liminality, is trickier to manage due to its greater abstraction. Its enmeshment in the cosmic structure of the universe is greater than duality, which, although also enmeshed in the cosmic structure, is easier to understand in isolation. The vertical duality cannot benefit from the same rhetorical and pedagogic vacuum.

This is because, by accessing a vertical hierarchy, the hexagram accesses a principle from the bottom of manifestation to the cosmic source at the top of Reality.

This is where the Hermetic interpretation comes into play, as the ability to act in accordance with a principle is hugely influential on historical magical and alchemical practices. This idea is that you can convert the expression of a principle on one level to another, as in calm skies to calm seas to calm hearts, via structured sympathy. Likewise, you could convert an expression on one level up into abstraction and then again into another expression on the scale of the first expression. Such an example would be boiling water to access the principle of “boiling,” to “boil” the blood of another person, and curse them with fits of rage. (The previous is different from straight sympathetic magic in that it acknowledges, through the hexagram, that “boiling” is a principle of the cosmic structure above the manifestations.)

We know it looks like the same thing with an extra step, but that extra step is suggestive of an entire cosmic structure that can be navigated/accessed.

V. Numbered Star Variations: The Heptagram

The heptagram, also known as the septagram, has two variants, both of which are regular and unicursal.

As you can see, one (acute, right) is spikier, and the other (obtuse, left) has much more open space within it for other workings.

This type of star is defined by the mysticism surrounding the number seven and its numerous observed correlations. It is associated with the seven planets and the seven days of the week. In alchemy, it is identified with the set of the four elements and the Tria Prima (sulfur, mercury, and salt), as well as the seven classical metals.

In Christian mysticism (formal and folk), seven is recognized as a number favored by God: seven virtues, seven gifts of the spirit, seven seals, seven churches, seven trumpets, seven angels, etc. Even the later rhetorical development of the seven deadly sins is intertwined with this numerology. For these reasons, the Christians have found occasion to employ the heptagram as a protective ward.

In Kabbalistic practice, it’s associated with the sephira of Netzach, which has a literal meaning of “victory” but is used to convey “eminence,” “everlastingness,” “perpetuity,” and similar concepts. In other words, it references the enduring immortal principle of a thing.

In Islamic mysticism, it is associated with the first seven verses of the Koran and the seven circumambulations of the Kaaba.

In the East, it has been associated with the seven levels of heaven and the seven levels of hell in Hinduism, as well as with the seven steps taken by the Buddha immediately after his birth.

In more modern Neopagan practice, it is heavily associated with faeries. According to symbolsandmeanings.net, it is often interpreted as a gateway between the world of the fae and the mundane. Additionally, in the anthropomorphic interpretation, the two surplus points are identified by practitioners of faerie magi with faerie wings (make of that what you will).

In his system of Thelema, Aleister Crowley identified the heptagram with his Gnostic interpretation of the mother-goddess, Babalon. Observe how he uses an inverted heptagram for his "Mother of Abominations."

|

| Very scary, much frighten. |

In our own research on the topic, we have noticed a consistent trend in the seven-pointed star’s association with the celestial.

The world over, seven is a popularly auspicious number (as already related), and that quality is substantively tied to the heavens in the organization. Civilizations have generally settled on the seven-day week or adopted it, often around the organizing principle of the seven classical planets: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These seemingly independent celestial bodies were identified with deities.

It is the observation of this Compiler that, as a practical matter, this set of seven planetary gods serves as a functional stand-in for the entire pantheon, encompassing the whole organizing structure of the heavens and, consequently, all of their influences.

This observation is not unique to us. Even the less rigorous source that is symbolsandmeanings.net, relays exactly this belief:

“While the five-point pentagram represents earthly magic, the heptagram/septagram is thought to be closely associated with celestial magic.”

The heavenly associations of the seven-point star seem quite common even in relatively low-resolution interpretations, which suggests it’s the naturalistic, instinctive connection to make. Given that gut-feeling reactions to the aesthetics of geometric figures are a valid basis for magical consideration (magic is not a rational art), we believe this instinctual reading is likely the most accurate interpretation.

This totalizing description of the celestial carries over into Monadic religious traditions and their subsidiary occult practices. In the Christian sphere of occultism, this is maximized in the Sigillum Dei, the seal of the “true name of God.”

Several hexagrams and heptagrams purport to be the “Seal of God,” like this one:

|

| The Seal of God as it appears in the Peterson translation of the Liber Iuratus Honorii. |

We’re not particularly interested in these because the field of divine-seal heptagrams has been dominated by one formula: John Dee’s 16th-century Sigillum Dei Aemeth.

|

| John Dee's version. |

Like Lévi, whose Baphomet was a refinement of the earlier Rebis of alchemy, Dee’s icon is a correction based on his dissatisfaction with previous formulas.

We’re going to take a moment here to point out that this sort of “correction” is relatively common in this field. People examine earlier formulas with different priorities, make connections that others haven’t, and then seek to improve or correct them.

This is normal, and this blog project is in part motivated by the same impulse.

We caution, however, that this impulse rarely helps you actually understand the material you’re reading. When examining historical sources, you have to take them as they are, especially if your corrective impulse impedes you from interpreting the material as it was intended to be interpreted. While innovation and creativity are great, especially in the development of fictional works and visual arts, they do not give you authority over the record. There is no “fixing” the works of Honorius of Thebes or the talismans of Pope Leo III.

Returning to the Sigillum, Dee’s version was constructed of a series of heptagons, a primary heptagram, and a central pentagram. How the numerous names of the seven angels of the planets, the seven angels before the presence of God, seven more planetary spirits, and all are based on formulations of 7x7 letter grids and the Kabbalistic Shem HaMephorash, the 72-syllable “true name of God.”

This device is incredibly complex and heavily informed by the angelic Enochian language, as confabulated by Edward Kelly. Its breakdown would require its own article, which has been done by others.

While we will eventually provide a full breakdown of this seal, we strongly encourage our readers to investigate it themselves, as it’s informative about how the various choices in complex pentagram construction might be made.

The pentagram (holotype) is optimized for the manifestation of earthly phenomena. The hexagram is optimized for dualistic expression, highlighting commonalities in opposing or contrasting subjects or vertical liminality along the axis of principle.

With the celestial qualities of the heptagram, especially its property of pantheon or grand set summary, the heptagram has access not just to multiple principles but also to the structures that connect them. This places the heptagram in a unique position, allowing it to reach into the dynamic operations that underly or transcend material reality.

While we suggested, in our hexagram musings, that it could be used to translate phenomena into new expressions along the same axis of principle, the heptagram might be used to translate one principle into another by identifying a translation mechanism through the planets, gods, or principles.

Under this interpretation, the heptagram is an actual mechanical formula for the translation of unlike things. For example, with the hexagram, an intense bonfire might be translatable to arson at a distance (in the literal) or inflamed passions (in the abstract), but a heptagram might be able to translate the intensity of that heat to a building’s structural integrity in a storm, or safety at sea, or good business prospects, by passing the performance through a celestial machine of cosmic principle-inputs.

VI. Other Basic Shapes

We provide an overview of other basic shapes that appear in these magic circles here. This is not exhaustive, as these shapes have many associations of their own, which will be examined in our [numerology] article.

The triangle is substance and manifestation. Or referential to God. It has trinary qualities based on its points and binary qualities based on orientation. Most of the information was already covered earlier in this article. Orientation indicates whether the shaping or generating forces are being invoked.

|

| The classic SATOR/ROTAS square. |

The square is an emblem of stability, typically interpreted as masculine/shaping relative to the circle’s feminine/generative. In the East, it is often associated with the element of earth. When laid over itself, it produces a regular but not unicursal octogram. Magical squares are placed around the magic circle for various reasons, though the numerology suggests this is to “stabilize” the circle. Also, when arranged with the corners positioned top to bottom, the diamond orientation remains identifiable as a square.

Circles within squares are a little less clear in meaning, though, as is often the case, these are more particular devices, such as letter grids, as seen in the Clavicula Salomonis.

|

| The First and Second Pentacles of Saturn, from the Clavicula Salomonis. |

These have more explicit mathematical formulas at work and may be referential to the magical [SATOR/ROTAS] square (an occult formulation with adjacency to the “true name of God”).

When laid in between each other, they form Aristotle’s transmutation square:

This Compiler has already voiced our issues with the Aristotelian elemental model, but it’s as valid a frame as any other, and we see it expressed well in storytelling.

|

| A basic demonstration of Alchemy in Fullmetal Alchemist. |

Another relevant relationship is that the square might, through the contextualizing symbols of the ruler and the compass, become a symbol of the impossible. A conundrum in mathematics that was referenced in alchemical practice was the impossibility of “squaring the circle,” or using only a compass and ruler to produce a circle and a square of identical area in a finite number of steps.

The task was proven impossible in 1882 by Ferdinand von Lindemann due to the transcendent qualities of π (pi).

Our computers have since been able to approximate squaring the circle by brute force to an arbitrary level of precision, but no such formula exists to accomplish the task. The phrase remains an identification of the impossible.

Whether this stymies magical operation in your storytelling or magnifies it through identification of the impossible with the divine, that’s up to you.

We’ve already covered circles in this very article, but it’s worth pointing out that circular relationships can be more complicated, namely by reversed arcs.

|

| The Fourth Pentacle of Venus, Clavicula Salomonis. |

Observe that in the Fourth Pentacle of Venus from the Clavicula Salomonis that the interior of the circle is marked by four quarter-arcs, which suggests presences external to the magic circle poking their way in or a more interesting interpretation: reflection and refraction.

Let’s look at an instance from fantasy media:

|

| Human Transmutation Circle from Fullmetal Alchemist. |

This is the human transmutation circle used by the Elric brothers in Fullmetal Alchemist when they attempted to bring their mother back from the dead as a homunculus.

Notice that there are six described materials around the circle, flowing into three filtering mechanisms that share a complex relationship to a reflected/inverted circle cut into thirds before manifesting in the central circle.

Anyone interested in picking that apart might want to try poring through Fred Getting’s Dictionary of Occult, Hermetic and Alchemical Sigils (1981).

Bars and crosses, as seen in the Sigillum and numerous other pentagrams examined so far, appear referential to a higher principle not necessarily articulated in the geometry, to highlight relationships across a complex diagram, or even to just make it very clear this thing is definitely magic.

|

| This is magic, in case you were wondering. |

VII. Abstract and Representational Imagery

There are other considerations beyond just pure geometry: the creative inclusion of letters, abstract figures, and representational images.

We’ve seen plenty of letters on our pentagrams so far. Usually, they’re listing the name of a spirit, deity, or other supernatural intelligence. They may be acronyms for divine names, which are synonymous with the abstract principles that govern action and phenomena in the world. They may also serve as a substitute for other abstractions.

We’ll demonstrate simply how this might be put into effect. Suppose we’re developing a pentagram and want to associate it with the Abrahamic divine. We have then decided to employ the Hebrew Heh (ה) as a reference to the divine exhalation of God.

|

| The whole world of phenomena is but an utterance from the mouth of God. |

The implication is that the practitioner desires/believes their operation is in line with the Word or wishes to sanctify their action by this intent.

We note that this may also be a violation of the 3rd Commandment (“Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain”) by identifying an evil magical operation with the Word of God. Not a very smart thing to be doing when operating in an Abrahamic framework.

Eight-spoked wheels are relatively common in the Solomonic tradition, as evidenced by numerous figures in the Clavicula Salomonis.

|

| The Seventh Pentacle of Jupiter, Clavicula Salomonis. |

These wheels are characterized by eight spokes, which may be indicative of the cardinal and intercardinal directions. It’s essential to remember that, even in the modern era with planes and trans-atmospheric flight to orbit or the moon, most of us navigate across this round Earth as a two-dimensional disk. These spokes, if directional, indicate forces coming from various quadrants, which might be the winds, timely constellations, or domains identified with supernatural spiritual figures according to belief or custom.

These spokes may terminate in or be marked along the length by symbols of any source. They might be alchemical, astrological, runic, Ogham markings, numerological notation, and so on.

Abstract shapes that roughly resemble identifiable icons are viable in the pentagram meta. Take, for example, the Seal of Solomon from the Ars Goetia.

|

| From the First Book of the Lemegeton, the Ars Goetia. |

This particular seal is purportedly useful for binding a demon or spirit into a brass vessel. This gives us a framework for interpreting the central features of the seal.

First, we have a cross in the background, represented by a vertical and horizontal line. This is a common emblem of earth or salt (materiality). The second version of the seal, on the right, also clarifies that the central forms are placed upon the sphere of the earth by the bottom curvature.

Our central figures are composed of a vertical monolith that is roughly phallic in shape. However, when interpreted as a negative space, it more closely resembles a classic keyhole to our eyes. This keyhole forms a vertical axis with a bowl and a flat surface.

We interpret the bowl shape as the vessel and the horizontal bar as the pentagram/stage of action in the conjuration.

This identifies an axial binding relationship between the world of matter, as a specific place, and the table, extending into the vessel. It’s a diagram of the binding itself!

This reading is valid on the basis that the classical keyhole for iron locks appeared sometime between the 12th and 14th centuries. At the same time, the Lemegeton, from which the seals are sourced, was compiled between the 14th and 15th centuries, meaning it would have been part of the cultural iconographic language by that point.

We’ve discussed representational imagery in our previous article, but not specifically about what representational images can mean.

Rather unhelpfully, they can mean anything.

If you remember the Second through Fifth Pentacles of the Moon from the Clavicula Salomonis, they’re just arms pointing at some script.

|

| The Second, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Pentacles of the Moon, Clavicula Salomonis. |

These are composed of a versicle (usually from a Psalm) and divine names of God and angels. Context clues suggest that, by the authority of God, the identified angels will confer the described knowledge and protections per the versicle.

In the case of the Fifth Pentacle of Mars, the figure of the scorpion (likely astronomical) is identified as “terrible unto demons, and at its sight and aspect they will obey thee, for they cannot resist its presence.”

|

| Fifth Pentacle of Mars. |

The versicle is as follows:

"Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet."

—Psalm 91:13

This tells us that the compiling sorcerer identified Scorpio, or the angel(?) HVL (who presumably presides over Scorpio), lays demons low like the lion and the serpent in the verse.

Next is the First Pentacle of the Sun:

|

| Hi-diddly ho, neighborino! |

In our previous article, we were in error, as the “Countenance of Shaddai the Almighty” is not interpreted as the face of God but instead the face of the angel Metatron, his mystic representative.

While not a literal interpretation of the face of God, it is a literal interpretation of the face of the transformed prophet Enoch. In this tradition, he is masculine to the feminine Sandalphon, who is the similarly transformed prophet Elijah.

With this in mind, this is an emblem of the divine shaping Will of God, “whose aspect all creatures obey, and the Angelic Spirits do reverence on bended knees.” This suggests the use of this pentacle is in the commanding of animals and angels.

VIII. Mandalas and other Cosmograms

Religious and magical cosmograms are not the exclusive purview of the West. We’ve already discussed the Shatkona yantra, which is a kind of mandala.

|

| Sri Yantra Mandala. |

This supports our position that loose categorical terminology is the human norm rather than the post-Enlightenment impulse to confine everything in hyper-precise, pseudo-scientific/pseudo-legalistic language (yes, this Compiler has personally had someone tell us that “proper” magical terminology is akin to “legal language”).

More important to this article is that the loose application of terminology applies to what is effectively the same functional category of icons.

Use in the East is noticeably different, with a greater focus on mandalas as devices for meditation and religious initiation, where one achieves a more profound understanding through the contemplation of their patterns.

Western pentagrams appear more blunt in their clear description of forces (classic pentagram and hexagram) and obfuscate meaning through code in magical operations. This is because, in the West, especially in religious iconography, visual harmony is achieved through narrative reference, classical Greek and Roman artistic sensibilities, and sacred architectural geometry. That’s not to say that Eastern values of harmony aren’t expressed in art, sculpture, and architecture. Instead, it highlights that the role was already filled in the West, which pushed the device into fringe practice.

In the East, meditative geometric mandalas are most definitely part of their normal spiritual toolkit. With a more open religious framework and no monolithic religious corporation like the Church, there was more room for geometric exploration of visual and aesthetic harmony and balance in embellished geometry.

These devices are widely used in folk magic for protection, healing, love, wealth, and prosperity, among other purposes, at the individual, household, and even community levels.

This reveals that pentagrams and mandalas are entirely the same iconographic category, even if the relevant cultures have slightly different relationships to the symbol family. Relevant to writers of fantastical fiction, this offers a shared iconographic language between magicians with different “dialects.” Characters might be surprised by a foreign magician immediately understanding their secret formulas completely by a foreign pattern recognition. Alternately, a magician may have a mostly accurate assessment of the foreign magic devices they’re working with, only to be thrown off by a subtlety internal to the culture.

Conclusion and Takeaway

Pentagrams and the family of cosmograms at large are functionally universal and ripe for exploration, deconstruction, reconstruction, and invention by enterprising storytellers. They’re versatile at all levels of storytelling resolution, and with the right attitude, they can be made to work for you. Whether it’s the development of magical systems, explorations of your setting’s cosmic structure and hierarchy of values, or your work’s visual language, the pentagram warrants your consideration. Their every shape, line, and curve can be set to work not only in the world of the narrative but also to establish communication with your audience, engaging them with numerous layered meanings simultaneously, inviting them to embark on a journey of understanding in tandem with your characters.

With the pentagram thoroughly deconstructed, we next move to the historical magical practices most commonly associated with it: [conjuration and sorcery].

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

CONSIDERATIONS FOR WRITERS

Here, we share our musings and story ideas we developed throughout putting this article together. These did not fit nicely inside the main body of the article, as they would be too disruptive to its flow, and so have been placed here at the end, where our readers can consider them in light of the above.

These are open for anyone to use, and we hope they will help get your creative juices flowing.

The pentagram has numerous post-hoc interpretations. The upper points of the inverted pentagram are perhaps the most notable example, but numerous others exist. In our previous article, we touched on a Jewish folk origin that associates the five-pointed star with the five books of the Torah. Likewise, the “Marian mark” apotropaic interpretation views the pentagram as five overlapping “V” shapes, referencing the Virgin Mary.

Rather than dismissing these later readings, we encourage our readers to view them as a creative process that can be leveraged for their benefit. Old symbols may have new life in your fictional world’s present thanks to this sort of living reinterpretation. This could be a source of dramatic tension if the true origins of the symbol are repressed or something convenient to exploit when moving icon-marked contraband.

Then there’s the dimension of identity. A shared icon may have competing interpretations based on group affiliation. While these competing interpretations need not drive the central conflict, they do serve as an excellent vehicle for communicating the group’s worldview. Further, acceptance or non-acceptance of the interpretive framework can reveal internal tensions within a group.

Taking the five books of the Torah, for example, one Jewish character can be rather insistent about reading Jewish or Hebraic origins into all manner of things. Another Jewish character in the same community might hear the five-books interpretation and say, “What a load of bupkis!” Further, who is dismissing the interpretation could well set the stage for a cultural conflict.

The motivated mystic could be relatively young. If their conflict is with an age peer, it could signify a cultural insecurity in the mystic that pushes them to accept flimsy fabrications to hold onto an idealized sense of tradition against a secularizing brother or cousin. If the person calling bupkis is older, it could be a conflict about the rashness of youth in the face of seemingly passive cultural wisdom and authority.

This Compiler is fond of employing this as a dynamic, living motif, where people apply what is convenient to their circumstances, allowing academic and historical use to coexist alongside convenient or self-flattering folk applications. Our personal interest in employing this sort of iconographic diversity is that it permits the symbol to be omnipresent without becoming stale. Since this Compiler writes with the pentagram as a dynamic tool in the magician’s toolkit, our magician characters can actively engage and reframe things in their environment to produce novel magical action!

In any case, not all symbols need to be hidden. They can be engaged by characters personally, institutionally, publicly, mystically, and through the meta-narrative simultaneously. Engaging any of your symbols, icons, or motifs on multiple levels simultaneously is generally good practice. Always look for ways to integrate your devices into multiple layers of consideration that serve your story or art.

Throughout our research, we have observed numerous “fives” that can be interpreted within the pentagram. While we could go on forever about possible combinations, we will instead model a novel reading of “five” to demonstrate the approach rather than providing an exhaustive list.

First, we return to the “Five Vs” formulation. In the Marian interpretation, they stand for “Virgin,” as in the Virgin Mary. What if we interpreted that V differently? What if, instead, we read it as the Roman numeral “V” for “five?”

5 x V = 25

We can apply this logic in reverse:

25 = 5 x V = Pentagram

Let’s place this in an urban fantasy context, American for convenience. The savvy magician has abstracted his magician’s pentagram into a coin, the quarter.

|

| Many Tarot decks gloss the Pentacles suite as “Coins” to avoid "Satanic" misinterpretation. |

Not only does the coin function as a synonym for the pentagram through the Tarot suite, but its numerology supports reinterpretation into the ritual device of the eternal knot.

Our magician, whether a monster-hunting good guy like Harry Dresden or a malevolent occult baddie, can bring one of his most crucial magician’s tools with him everywhere he goes, hidden in plain sight! This also makes our magician particularly resourceful; if he loses his own magician’s tool, he can obtain a new one from other people, including those taken from cash registers and found on city streets.

And now that the door has been opened for coins to be used in practice, our magician might develop their own system based on coin denomination! We invite the reader to devise their own models for how this might work.

These sorts of ideas are exactly why we believe the deconstruction of magical iconography is so vital to storytellers. By understanding the possibilities of the constituent parts, you can rearrange them in novel ways that serve your stories and reward the audience for putting the pieces together.

Another dimension of the number five to consider is its relationship to the number four.

|

| The daring might suggest that four is only a step away from five. |

Okay, that’s worded a bit obtusely. What we mean is that there are plenty of standard sets of four: four humors, four material elements, four cardinal directions, etc., etc.

The elemental consideration should be most familiar to our readers, so we’ll stick with something in that general ballpark: the suites of the Tarot and the derived suits of playing cards.

Revisiting the name “pentalpha,” in both Tarot and playing cards, we have four Aces. Organizing these around the pentagram both suggests and invites the inclusion of a Fifth Ace. If all cards are in play, this doesn’t mean just a fifth Ace but an entire Fifth Suite!

Let’s work with that for a moment and clarify how we’re using the suites: a device to organize factions and their member characters. Under this model, the Aces are individual persons, as are the 2s, the 3s, the kings and queens, etc.

The Fifth Suite could refer to several things, such as an additional set of characters, an abstract state or point of rhetoric or philosophy, or an aspirational state of personal transcendence.

For our story, we’ll make a few decisions about how to employ this framing:

The Fifth Ace

The relevant world of the story is governed by powers and authorities divided into four factions based on the suits or suites in a system that has become oppressive and unmanageable.

|

| The Four Aces of the Waite Tarot. |

Our Fifth Ace is our story’s “chosen one” figure, who is responsible for revealing the Fifth Suites and reclaiming the positions of the Major Arcana, which have been fought over by and distributed among the suites.

Our hero, in the traditional Shounen style, originates from one faction but finds himself lacking in taking on one of the lesser arcana roles. With his Ace status revealed to him, he has to build his own suite, first by poaching a friend from his home suite, then by defeating and poaching members of other factions. As they develop under the Fifth Ace’s leadership, their numerical role in the Fifth suite is revealed as a transcendent property of the number position shared across all four initial suites, following the power-up progression conventions of Shounen anime. These characters continue this power-up progression as they interface with the powers of the Major Arcana, which are acquired by our heroes. (Some characters may hold onto certain Major Arcana as a matter of rightful possession, character development, etc., while others might be traded freely between our Fifth suite to meet novel challenges.)

As the Fifth Ace absorbs both the Major and Minor Arcana into his team, those ancient horrors responsible for imposing the system in the first place come out of the woodwork to preserve what they have created. This allows our heroes to continue fighting and incorporating other mystical and occult organizational frameworks into the plot and their character development as we complete the 78 cards. Alternatively, these figures can be a roadblock to the full integration of the 78 Arcana, and full integration requires the conquest of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life or a similar structure.

All of the above has stemmed from a simple observation that the “A”s of the “pentalpha” can be read in a novel way. From a single observation, we were able to construct a conflict, worldbuilding, and character progression in a manner that brings its own aesthetic suggestions to the table, ready to be interpreted by visual storytellers!

The more you exercise this sort of iconographic plasticity, the more you can develop this sort of rapid worldbuilding to develop stories on the spot or solve problems in the extant stories you are working on.

Building on our connection between the hand-pentagram and Eastern media, we’re naturally led to consider the possible applications of Western occult iconography and practice when incorporated into an Eastern genre, such as Wuxia.

The Wuxia genre is a Chinese mystical sword fantasy featuring martial artists, alchemists, and sorcerers who manipulate the world and fight each other using qi martial arts, feng shui, mystical enlightenment, and performance-enhancing drugs.

|

| The Feng Shui Pentagram. If you don't understand this, we recommend this video. |

Eastern mysticism has its own pentagram, used in its five-element model of correspondences, but that doesn’t exclude the use of unusual methods in foreign lands. Characters might journey westward to acquire knowledge and techniques unknown in China, or foreigners may come bringing their strange ways to participate in the fantastical world of Wuxia’s jianghu (“martial forest,” literally “rivers and lakes”).

This opens many possibilities. Referring back to Buddha’s Palm from Journey to the West, the hand is a viable cosmogram. As the genre emphasizes martial arts and kicks, the foot is also a viable pentagram. It’s an appendage with a flat surface and five digits; why wouldn’t it be a viable pentagram analog?

The immediate route to take this is to transform the body and the four appendages into stages of the elements, allowing the practitioner of the Western occult-inspired martial art to readily convert their qi strikes into expressions of or controlling actions of the five elements, effectively making them a bender, like in Avatar: The Last Airbender, except multi-elemental (without being the Avatar).

Because “spirit” is less defined than the material elements, this could be further explored for novel effects. Perhaps it can interfere with the flow of opponents’ qi? What if it facilitates reaction and reconstitution like the transmutation circles of Fullmetal Alchemist? Or, we think more interestingly, this allows the martial artist to incorporate more abstract magic and sorcery into their martial arts.

Consider a relatively weak martial artist who goes to the West and learns Solomonic sorcery techniques. He might come back with a mastery of lamen, ritual shield icons that depict a demon’s seal and protect the magician from that demon. He might employ this against powerful yaoguai well above his level to handle and trounce them because they don’t have a counter.

Alternatively, a martial artist who learns Solomonic sorcery might employ the Seal of Solomon on his palms and soles, using it similarly to how it’s employed in the Testament of Solomon. Every time he strikes a yaoguai or other spirit with his palm or sole, they are bound to his service so long as he maintains certain ritual observances. This sorcerer can use this to accumulate an army of demons or use the number of bound demons to bolster his martial arts attacks with techniques like “One Thousand and One Fists.”

Beyond the pentagram, incorporating Western occult and alchemical traditions into Wuxia opens up numerous creative opportunities. Styles like “Wrath of Rubedo, Fist of the Crimson King,” “Crane Fist of the White Virgin,” or even “Green Lion’s Claw” interface not only with Wuxia’s martial arts dimension but also with its alchemical dimension. A Western-alchemy-influenced martial artist might call himself Alkahest, after the universal solvent, because he uses Western alchemical stimulants to slow his perception of time to break down his opponents’ styles and techniques, copy them, and then reconfigure them into his own body of martial arts knowledge.

While not directly related to the pentagram, we would be remiss if we didn’t tackle this upcoming topic, as we don’t have anywhere else to put it, and it flows directly from the Wuxia matter above:

Everything we have said of Western occult iconography and practice interfacing with Eastern media is true of Christian/Abrahamic influences.

Unfortunately, due to the typical proselytizing function of such media and the dominance of the child-friendly in the post-post-iconoclastic Protestant dominance of explicitly Christian media, all such endeavors will be read by modern audiences as, well, hokey.

|

| This will never be as effective as VeggieTales. |

Except, that is, in absurdist comedy.

Absurdist comedy prioritizes getting a laugh out of its audiences through a ridiculous formulation, and that formulation may not necessarily be respectful to the material. While this may be offensive in some instances, it can also produce something amusing to general audiences but hilarious to those in the know.

To explain this, we’ll present this in two formats: a Western parody comedy and a Japanese martial arts shounen comedy.

Zucker Style

In our Western parody, we lampoon the film The Exorcist (1973). During the exorcism, the demonically possessed girl breaks free from her restraints and hits the officiating priest square in the face with a crane kick. The priest, losing his patience, declares he’s going to kick the Pazuzu’s ass and engages in a series of katas before declaring his use of “Five Sacred Wounds Style.” The demonically possessed girl leaps from the bed and performs her own series of katas, identifying them as “Your Mother Sucking Cocks Style.” The two then kung fu fight all across the house, knocking holes in the walls, breaking every window, and smashing all the decorations.*

*(Compiler’s Note: This may have already been done. If so, it confirms our point.)